“…the only place on earth where all places are — seen from every angle, each standing clear, without any confusion or blending" El Aleph, Jorge Luis Borges

From Crowdsourced point clouds to 3D Maps

By Patricio Gonzalez Vivo

The following is a brief documentation of my research on point clouds as a way to crowdsource mapping and the tools I made along the way. This serves as a prove of concept that points to a future where people can contribute to open source initiatives with minimum effort and skills.

Working with Point Clouds

Point clouds are not new, but they are trending because new devices with more computational power and memory make point cloud tech more accessible. From video games to the big screen, more and more points are being generated.

LIDar data

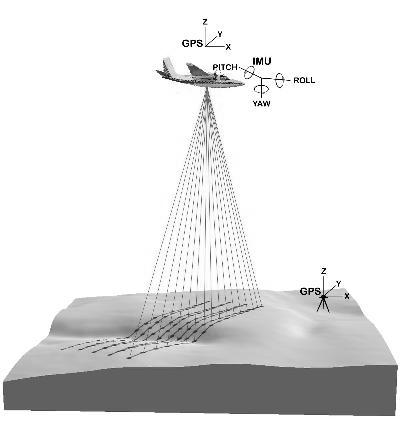

Not too long since the invention of lasers in the ’60s, scientists have been mounting laser scanners under planes to sends pulses of light to a surface and measure the precise distance to it. Together with the geolocation of these points this technology is known as LIDAR.

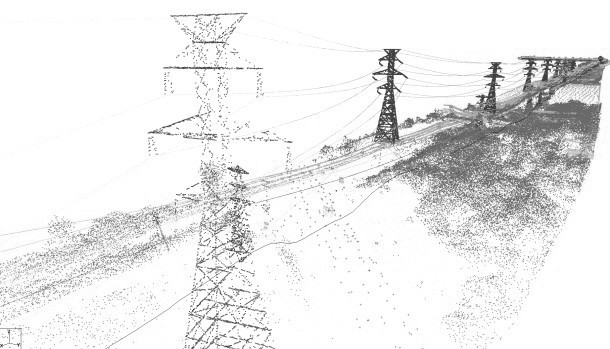

In the last years a new generation of smaller LIDAR devices have come to the market. They can be mounted on cars and backpacks, preserving every single point from a particular place - like holographic glass snow globes.

According to the closing law of gestalt psychology human perception is very good at making sense of these clusters of dots. Our mind completes the empty spots. The more point of view the sources have, the closer the map looks to the terrain.

In order to work with LIDAR data, you first have to merge and clean it. There are a couple of programs that help you do this at this scale; the best open source application I found was CloudCompare.

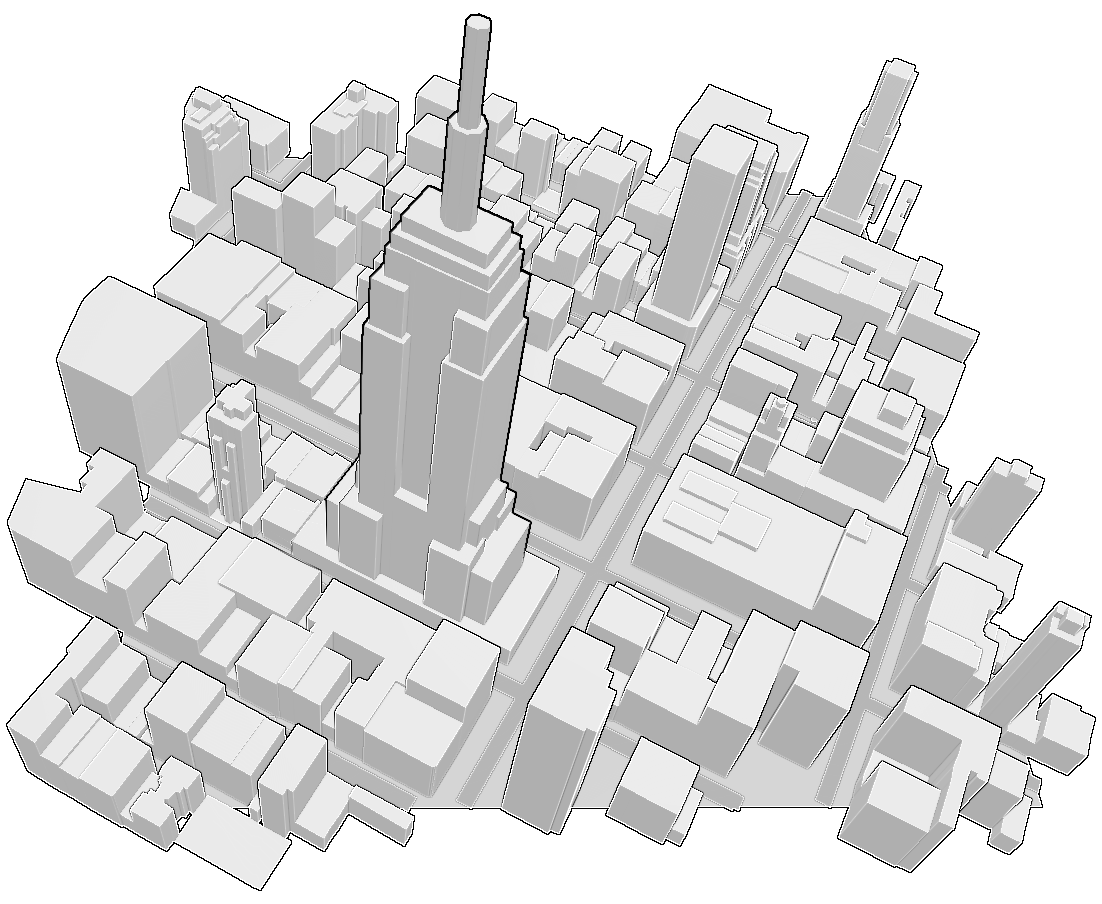

Thinking bigger also means thinking about serving and analyzing this information, for that loading the points to a GeoSpacial database is crucial. PostGIS can be use to cross this information with any map. An example of that process is this tutorial from Yuriy Czoli were he uses the altitude of points to set the height of building on OpenStreetMap.

In my case I was interested in creating ways for OpenStreetMap polygons to look more accurate.

Coming from an artistic approach, I made my own way into this technology. First making some scripts to convert Lidar data to other formats, export them to PostGIS and extract single buildings or tiles from them.

All of these tools you can find at this Lidar-Tools repository:

-

las2SM: re-project lidar files (.laz/.las) to Spherical Mercator (epsg:3857) -

las2tile: crop a tile from a lidar file (.laz/.las) and project to Spherical Mercator (epsg:3857) -

las2ply: export lidar files (.laz/.las) into .ply format getPointsForID: once a PostGIS database is loaded with lidar information of a region, this script gets all the points inside a tagged OSM polygon by providing the OSM ID.

Making point-clouds from pictures

But, who owns a Lidar anyway? They are expensive devices, that only companies and institutions can afford. As far as I know thats how “open” this technology is.

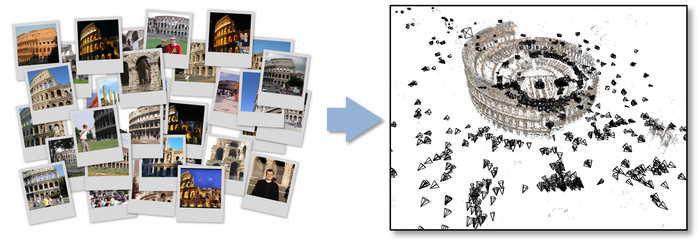

There is a way to achieve similar point cloud results without Lidar: a relatively “old” technique call photogrammetry that requires just a regular camera and some patience (especially to compile the available open software). Photogrammetry was originally developed in 2006 under the name of PhotoTurism. It stitches photographs together, finding distinctive assets and cross similarities to then construct 3D point clouds.

Today the most most popular applications using this technology are PhotoSynth and 123D Catch. The are also some powerful open source equivalent such us Bundler and VisualSfM.

“Bundler takes a set of images, image features, and image matches as input, and produces a 3D reconstruction of camera and (sparse) scene geometry as output. The system reconstructs the scene incrementally, a few images at a time, using a modified version of the Sparse Bundle Adjustment package of Lourakis and Argyros as the underlying optimization engine. Bundler has been successfully run on many Internet photo collections, as well as more structured collections.”

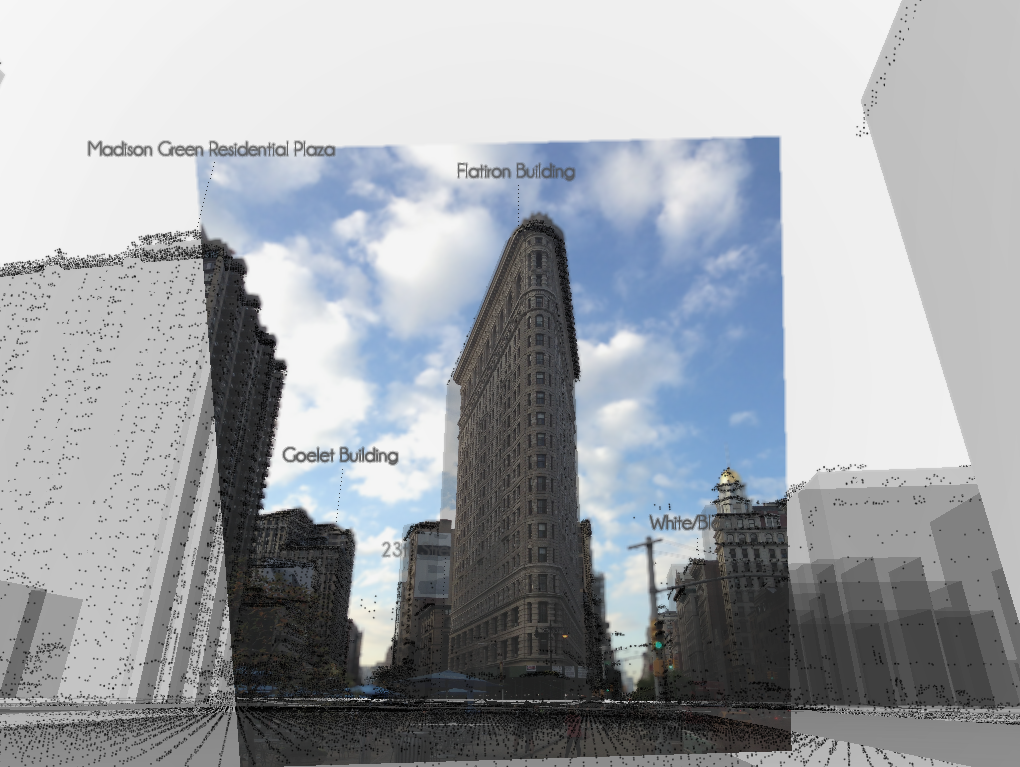

My fieldwork began with taking pictures of the Flatiron. I followed Jesse’s tutorial to learn how to take better pictures, how to process them with VisualSfM and clean the dense reconstruction with MeshLab.

I found this to be a really smooth and flexible work flow. Pictures can be taken in different moments of the day and with any camera. In my case I finished adding a bunch of them with my cellphone because I was interested in using the geo position from the GPS, which ended up being a whole new problem.

The results of the above process are: a point cloud of feature markers that contain information from the cameras called bundle.rd.out (from the bundler algorithm ) and a big point cloud product of the dense reconstruction (from the pmvs2 ). Both files are coherent between each other. They share the same space coordinates. You can load them and experiment with them using this addon for openFrameworks. In order to import this data constructed just from photos to a PostGIS server I had to find a way to geo reference the point clouds.

After taking more photos width my cellphone and using the GPS location hidden on the EXIF header, I was able to extract the centroid, approximated scale and base rotation to level the cameras over the surface. The final adjustments (translation and precise orientation) were made by hand. The reason for that is the incredible noise in GPS data thanks the well know “urban canyon” effect that makes satellite signals bounce between buildings.

On the following images you can see the result of this process. The Flatiron points, photo images and extruded OSM polygons are displayed together. The abstract universe of maps os contrasted side by side with photographs and virtual points.

From Point Clouds to Meshes

Once I got a coherent universe of point clouds correctly geolocated, it was time to load them to my PostGIS database together with our OSM Metro Extracts. For that you can follow this short tutorial. The reason to load the OSM Metro Extract? You can use PostGIS geo-spatial query functions to extract with surgical precision a specific feature. For example the “Flatiron Building” or node:2517056822. Inside the repository LIDar-Tools you will find a Python script call getPointsForID that will let you do this extraction with out knowing how to make a PostGIS Query.

With all the points of the Flatiron I was able to perform a Poisson Reconstructive Algorithm (using CGAL’s implementation) to construct a mesh from the points. Once again you can find this tool at the LIDar-Tools repository in the sub folder called xyz2Mesh. Alternatively you can use MeshLab’s, but I found that CGAL’s implementation works better.

Meshes to GeoJSON Polygons

Although I love how meshes look, they have too much information for what OSM can hold. This last step in the process is about downsampling the information we collect to something that can be uploaded and shared on the web.

OSM database doesn’t know much about 3D Meshes. Basically all buildings are polygons with altitudes. Like layers of a cake, polygons sit one on top of another. In order to make our mesh compatible with OSM we have to cut “slices” as cheese. In this repository you will find a program that does exactly that. Slice the mesh inch by inch, checking every slice with the previous one, if it finds a significant change on the area size, it adds that cut on top of our cake.

Conclusion

For this process I used an extraordinarily convenient sample. Beside being a beautiful building, The Flatiron is perfectly isolated construction. To apply this process to other buildings extra steps have to be add to this pipeline. This was a proof of concept investigating the potential of mixing lidar information with SfM reconstructions as a way to crowdsource point clouds - one that points to a future where people can contribute to open source initiatives just by sharing their pictures.